-40%

Civil War CDV Union General Regis de Keredern De Trobriand Gettysburg Commander

$ 184.8

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

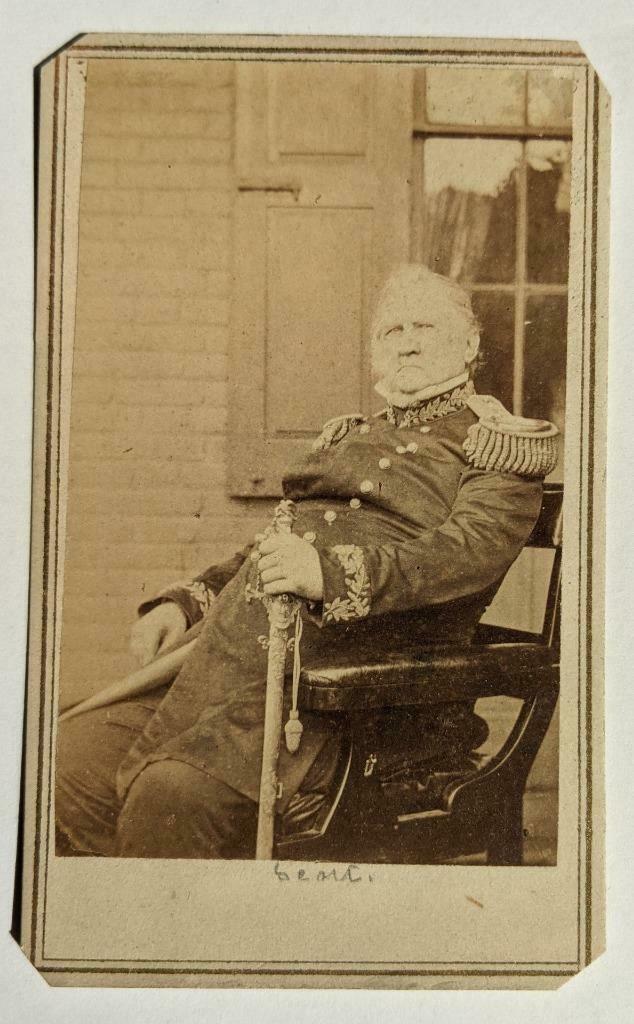

Condition as seen. "Philippe Régis Denis de Keredern de Trobriand (June 4, 1816 – July 15, 1897) was a French aristocrat, lawyer, poet, and novelist who, on a dare, emigrated in his 20s to the United States, settling first in New York City. During the American Civil War, he became naturalized, was commissioned and served in the Union Army, reaching the rank of general.

While serving as the commander of Fort Stevenson in Dakota Territory from 1867 to 1870, he was promoted to the brevet grade of brigadier general in the regular army in 1868. During Reconstruction, Trobriand was part of the occupation forces in Louisiana and was based in New Orleans, where he lived from 1875 on, retiring from the Army in 1879.

Contents

1

Early life

2

Civil War

3

Postbellum service

4

Later years

5

Legacy and honors

6

Books

7

See also

8

Notes

9

References

10

Further reading

11

External Links

Early life

Trobriand was born at Chateau des Rochettes, near Tours, France, the son of Joseph de Keredern de Trobriand, a baron who had been a general in Napoleon Bonaparte's army, in a family with a long tradition of military service.[1] His mother was Rosine Hachin de Courbeville.[1] In his youth, Trobriand completed a baccalaureate at the College of Saint-Louis in Paris, followed by studying law. He wrote poetry and prose, publishing his first novel, Gentlemen of the West in 1840 in Paris. His father's service to the previous king, Charles X, meant that Trobriand was excluded from serving the new one, Louis Philippe, after the July Revolution of 1830.[1] Trobriand became an expert swordsman who fought a number of duels.

In 1841, to answer a dare, Trobriand emigrated to the United States at the age of 25 and immediately became popular as a bon vivant with the social elite of New York City. He published his second novel, The Rebel, in New York in 1841.[1]

He married heiress Mary Mason Jones, whom he met in New York, where her father Isaac Jones was a wealthy banker; their wedding was in Paris.[1] After they lived in Venice for a time, socializing with the local nobility, they returned to the United States. They took up permanent residence in New York. They had two daughters, Marie-Caroline and Beatrice.[1]

In the 1850s Trobriand earned a living writing and editing for French-language publications. He was the editor and publisher of Revue du Nouveau Monde (1849 to 1850) and joint editor of Le Courrier des Etats-Unis (1854 to 1861).[2]

Civil War

After the Civil War broke out, Trobriand became a naturalized citizen of the United States and on August 28, 1861, he was commissioned as an officer and given command of the 55th New York Volunteer Infantry, the predominantly French-immigrant regiment known as the Gardes de Lafayette. He and his regiment were attached to Peck's Brigade of Couch's Division, Keyes's IV Corps of the Army of the Potomac in September 1861.

They took part in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, seeing first combat on May 5, 1862, at the Battle of Williamsburg. Soon after, Trobriand was debilitated with a malady diagnosed as "swamp fever", missed the remainder of the campaign, and was unable to return to duty until July. His regiment's next engagement, part of the brigade of Brig. Gen. J. H. Hobart Ward, III Corps of the Army of the Potomac, was at the Battle of Fredericksburg. They were held in reserve and escaped the terrible bloodshed of the Union defeat.

In December 1862, the 55th and 38th New York were merged, and Trobriand became the colonel of the now-named 38th. He led his new regiment at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, but was not heavily engaged. After the III Corps was reorganized following its severe casualties at Chancellorsville, Trobriand was given command of a new brigade.

Trobriand's military career is best known for the Battle of Gettysburg, where he first saw significant action. He arrived on the second day of battle, July 2, 1863, and took up positions in the area known as the Wheatfield. His brigade put up a spirited defense against powerful assaults by Confederate Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's division, particularly a Georgia brigade under Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson and a South Carolina brigade under Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw. They successfully held out until relieved by units of Maj. Gen. John C. Caldwell's division of the II Corps, but it came at a terrible price—every third man in Trobriand's brigade was a casualty.

After the battle, his division commander, Maj. Gen. David B. Birney, wrote:

Colonel de Trobriand deserves my heartiest thanks for his skillful disposition of his command by gallantly holding his advanced position until relieved by other troops. This officer is one of the oldest in commission as colonel in the volunteer service [and] has been distinguished in nearly every engagement of the Army of the Potomac, and certainly deserves the rank of brigadier-general of volunteers, to which he has been recommended.

— David B. Birney, Report on Battle of Gettysburg

Despite the recommendation and his excellent performance at Gettysburg, Col. Trobriand did not receive a promotion to brigadier general until his appointment to that grade by President Abraham Lincoln on April 10, 1864, to rank from January 5, 1864, after the U.S. Senate had confirmed the appointment on April 7, 1864.[3] He finally assumed command of a brigade to match his rank when Brig. Gen. J. H. Hobart Ward was dismissed from the Army for intoxication.

Late in the war, Trobriand occasionally led a division during the Petersburg Campaign and the Appomattox Campaign, especially when Gershom Mott was wounded in the latter campaign. On January 13, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated de Trobriand for the brevet grade of major general to rank from April 9, 1865, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the nomination on March 12, 1866.[4] De Trobriand was mustered out of the volunteer service on January 15, 1866.[3] On December 3, 1867 President Andrew Johnson nominated him for the brevet grade of brigadier general in the regular army, to rank from March 2, 1867 and the U.S. Senate confirmed the award on February 14, 1868.[5]

Postbellum service

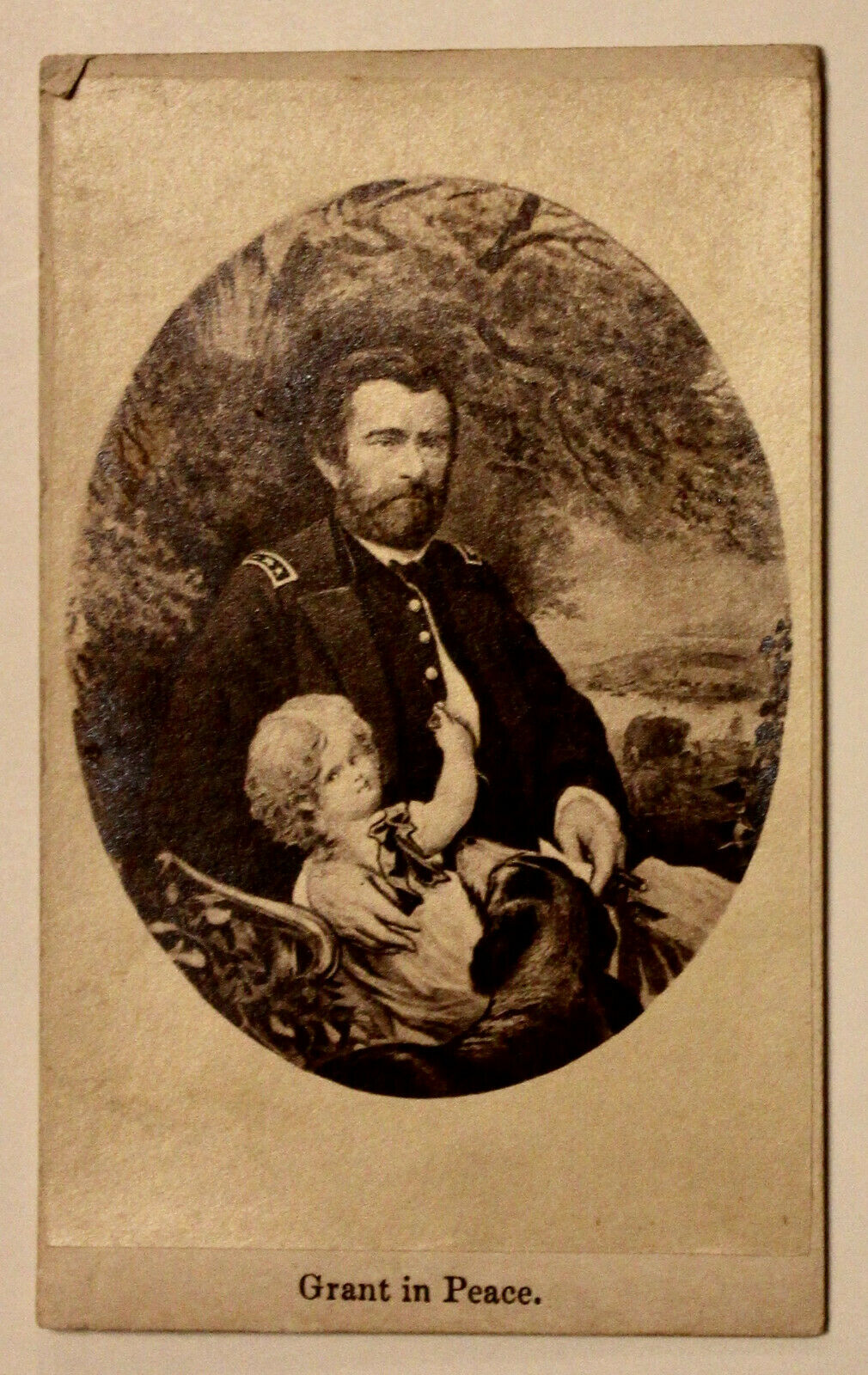

Trobriand returned to France, where he intended to write about his experience with the Union Army. In November 1866 he received word of having been appointed by General Ulysses S. Grant as colonel to command the 31st Regiment of Infantry, but requested a leave of absence to complete a book about his war experiences and the Army of the Potomac. This was already underway, and he published Quatre ans de campagnes à l'Armée du Potomac in 1867 in Paris and in the US that year (the English translation, Four Years with the Army of the Potomac, was not published until 1889). The leave of absence was granted until July 1867.[6]

Trobriand returned in 1867 to serve with the US Army in the West, where it became engaged in the Indian Wars. Trobriand commanded Fort Stevenson in Dakota Territory from 1867 to May 10, 1869.[1] Although his book was published in French in the United States, it was very favorably reviewed by American newspapers as the New York Tribune, Evening Post, Washington Chronicle, The Nation, and Army and Navy Journal; his American son-in-law sent him copies.[6] While in North Dakota, Trobriand painted a series of landscapes and portraits of friendly American Indians of the region: the Arikara, Gros Ventre, and Mandan peoples. Reproductions of 27 of his paintings are displayed at the fort today.[1]

He next served as commander of Fort Shaw in Montana, where hostilities had been high between settlers and members of the Blackfoot Confederacy, who had historically occupied the territory. He explicitly ordered protection of friendly bands, but the Army mistakenly attacked one in the Marias Massacre of January 23, 1870, to national outrage. Over the next few years, Trobriand also served in posts in Utah, during tensions with the Mormons, and commanded Fort Steele in Wyoming.

In 1874 President Ulysses S. Grant assigned Trobriand to New Orleans, as colonel to lead the 13th Regiment in protecting the state legislature and other officers of government due to repeated violence in the state related to the 1872 disputed gubernatorial election in the state. In September 1874, 5,000 members of the White League had taken over state offices in the city for three days, in an attempt to turn out the Republicans. They retreated before federal troops arrived in the city. Trobriand reached New Orleans in October 1874. On January 4, 1875, he participated in ejection of eight Democrats who were not certified by the Returning Board, but attempted to take seats in the legislature, and refused to leave. Trobriand did not act until after receiving explicit orders from Governor Kellogg.[7]

During this period of dissolution of the Reconstruction government, despite speeches against interference with the legislature, individual Democrats praised Trobriand for his delicate handling of the situation. But, the Democrats established a separate legislature, meeting from then on at the Odd Fellows Hall and committed to Democrat Francis T. Nicholls, whom they claimed as governor in the 1876 election. Stephen B. Packard, a United States Marshal, was elected as the Republican governor of Louisiana, and occupied the State House with the Republican legislators, but effectively controlled only a small part of New Orleans around the state buildings.[8]

After President Grant withdrew federal troops from New Orleans in January 1877, Trobriand accompanied them to Jackson Barracks, outside the city on the Mississippi River. Nichols used a militia to take control of the courts and police.[8]

Trobriand had minimal assignments from 1877 until retirement from the Army on March 20, 1879, and conducted training of soldiers and other daily routines at the Barracks. He was ordered to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in July 1877 to command federal troops there against labor riots in the Great Strike, but these were suppressed by city and state forces[9] after much property damage.[10]

Later years

In retirement, Trobriand and his wife settled in New Orleans, in rue Clouet of the French Quarter. For years, he cultivated roses in a large garden, and also enjoyed painting and reading.[11]

He wrote Vie militaire dans le Dakota, notes et souvenirs (1867–1869) (published posthumously in 1926 (in English as Army Life in Dakota); and Our Noble Blood(published posthumously in 1997). He and his wife spent their summers alternately with their daughters, Marie Caroline Post, who lived on Long Island in Bayport, New York; and Beatrice Stears, who lived in France.[12] With increasing age, he made his last trip to France in 1891.[13]

Trobriand died in Bayport and is buried in St. Ann's Episcopal Cemetery in nearby Sayville, New York. He was survived by his wife, two daughters, and several grandchildren.[1]

Legacy and honors

Marie Caroline Post, Régis de Trobriand, The Life and Mémoirs of Comte Régis de Trobriand: Major-general in the Army of the United States, New York: E. P. Dutton & Company, 1910 (Google eBook) (Biography by his eldest daughter, including collected papers of her father; extensive documents)

The de Trobriand Art Gallery was established in his honor at the Fort Stevenson Guardhouse near Garrison, North Dakota. It permanently displays reproductions of 27 of the general's North Dakota pieces.[1]

Four paintings and numerous sketches by Trobriand are held in the collection of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Several of Trobriand's oil paintings are part of its main exhibit at the Heritage Center in Bismarck.[1]

In North Dakota there is de Trobriand Bay on Lake Sakakawea located near Ft. Stevenson State Park where he served.

Books

Les gentilshommes de l'ouest (The Gentlemen of the West), published in Paris (in French) in 1840[1][2]

The Rebel (1841), novel, published in New York[1]

Quatre ans de campagnes à l'Armée du Potomac (1867), English translation, Four Years with the Army of the Potomac (1889)[1]

Vie militaire dans le Dakota, notes et souvenirs (1867–1869) (published posthumously in 1926 (in English as Army Life in Dakota)[1]

Our Noble Blood (1997) (published posthumously)[1]